Reviewing Every Book I've Ever Read

Attention Conservation Notice: For many of the books here, I no longer have an accurate recollection of their details. I’m relying on memories of memories.

The Martian Chronicles

Ray Bradbury

★★★★

I read this collection for a book club I was attending while living in Oklahoma City. This was one of the only books that all members managed to read significant portions of. Bradbury writes so simply and imaginatively that it makes you believe you could write short stories too. </span>

Man of Steel and Velvet: A Guide to Masculine Development

Aubrey Andelin

★

Was either required or recommended reading at the theological college I attended, and was quoted with the confidence as if Moses had brought it down himself from a third trip up Mt. Sinai. Andelin wrote this book in the 1970s and it contains the worst of the reactionary movements of this time. Homophobic, sexist, essentialist: reading this book may increase the likelihood of beating your wife.

The authors wife, Helen Andelin, wrote Fascinating Womanhood, a perfect sexist complement to this volume, and started the movement of the same name which went on to reinforce millions of (mainly American) women’s belief that housework and cooking in suburbia was not only god-commanded, but the only way True Women had historically lived. </span>

How to Read a Book: The Art of Getting a Liberal Education

Mortimer J. Adler

★★★

Overrated. That is not to say this is a bad book, and I certainly wouldn’t say that to Adler’s face. Unfortunately, How to Read a Book has been picked up by part of the self-help community, with promises of its brilliance way outpacing the books original scope. Any nerdy, voracious booklover is likely to pick up most of Adler’s techniques just by virtue of reading books and filtering to not read other books.

Some of the banalities include: reading the table of contents, skim-reading, situating the book within the context of other books it references. One wonders why Adler thought anyone willing to read through 400 pages on How to Read a Book wouldn’t already know the vast majority of its contents.

Adler, also a joint founder of the Great Books Movement, ends by giving us a list 137 recommended authors with only two women: Jane Austen and George Eliot. Charming. </span>

The Israeli Solution: A One-State Plan for Peace in the Middle East

Caroline Glick

★★

I read this book at a time where I had a very limited knowledge about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, or at least an extremely biased pro-Israel perspective. One can’t blame me for being brought up with this perspective, but perhaps we can blame Glick a little more.

The Israeli solution is exactly that: an Israeli solution for a Israeli-Palestinian conflict. One-state instead of two-state. Israel gets official hegemony and we just have to forget about the past. I’m sure any educated reader could see the problems with this book, but I certainly wasn’t at the time. Later, I read The Lemon Tree. It would have been beneficial to reverse the order. Two stars perhaps only in order to see what conservative Israeli’s say about the issue.

</span>

Kim

Rudyard Kipling

★★★★★

Kim is immersive and brilliant. Not many books I have read compete with the level of sheer enjoyment I had in following the Kim around. Kipling apparently has a legacy of perpetuating racial eastern stereotypes, but I am in no way qualified in judging whether Kim suffers from this defect. What I do remember were the most lively, engaging characters and being introduced to Buddhism and the Wheel of Life. This is a book I want to read again for the first time.

</span>

Mastery

Robert Greene

★★★★

Greene is a master of the historical biography and all the characters he introduced in this book were fascinating no matter my interest in the subject. I can remember walking around in my dormitory completing my cleaning duties fascinated by how Jean-François Champollion deciphered the Rosetta Stone, how Marcel Proust’s life prepared him for In Search of Lost Time, or how Temple Grandin created machines to handle animal stress.

If you’re looking to become a Master by reading Greene, you’re reading for the wrong reason. He seems to have either no knowledge of survivorship bias or has just convinced himself that if he just continues to act like it doesn’t exist, no one will notice. His protege Ryan Holiday follows the same script, pumping out book after book on how to Be Successful by mapping out the way other successful people did so. They’re both bestselling authors, a testament to the unimagineable selling power of telling people the only barrier to success is the right mindset rather than genetics and luck.

Mastery is just so good despite the dubious premise that the reader’s latent talent will get unlocked by a simple reading because the stories of its masters are too engrossing. Read it as history and not self-help.

</span>

Life of Charlemagne

Einhard

★★★

A short biography of Charlemagne, written by Einhard who was a courtier in the emperor’s court. Not recommended if you just care about learning about Charlemagne. I often found it hard to know when Einhard was exagerrating, how accurate his description of Charlemagne’s temperament was, or any of the useful surrounding information and modern biographer would provide. More interesting to me as a historiographical artefact than as history. </span>

New Testament Survey

Merill Tenney

★★

Was required reading for a class on the gospels I took while studying theology. The blurb describes it as a “comprehensive” survey, but unless you are an evangelical Protestant this is undoubtedly not true. It’s discussion of the problems of the origin and order of the gospels is at least a relatively accurate entry level introduction, but leaves out all of the interesting analysis and implications: i.e. if we have found out that Matthew and Luke are both just copying Mark, what does this really say about the supposed oral tradition? A book like this suffers from the fact that its audience is undoubtedly going to agree with it–Bible College attendees aren’t usually wanting to be told inconvenient truths about the book they worship. </span>

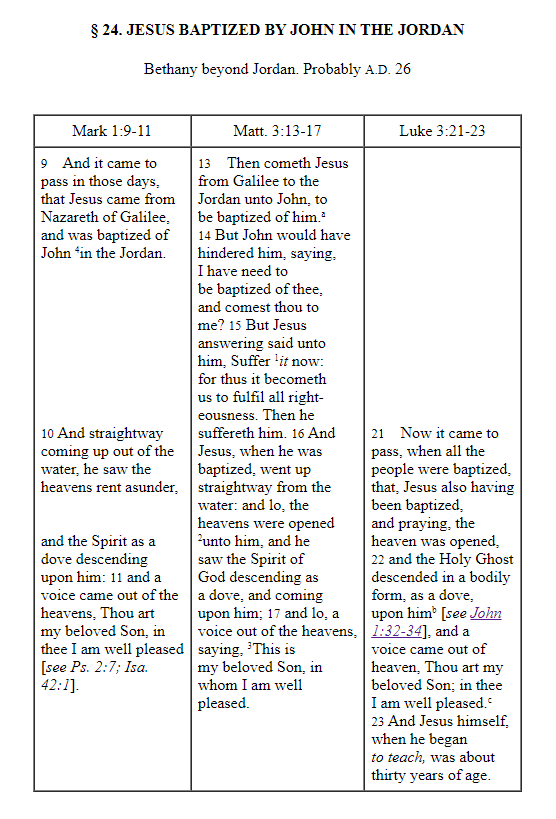

Harmony of the Gospels

A. T. Robertson

★★★

A genuinely interesting way to read the Gospels, if one cares to do so. Robertson lines up the different ways that the canon gospel writers tell the same stories in tables. If Matthew, Mark and Luke all tell the same story, we can see the similarities and differences in the telling.

The example above has been of particular interest to critical scholars, and if I had the knowledge I do now of the state of New Testament studies, this would have been a much more interesting read. In general Mark tells the story first, with the least embellishments. Matthew and Luke come along later, inserting what they believe to be neccessary theological additions. Finally, John, decades later, often tells completely different stories, but when he chooses one common to the Synoptic gospels, the Jesus he describes has leveled up. In the story above, where Jesus comes to be baptised by John the Baptist, Mark, writing first, describes how Jesus is baptised and the “Spirit as a dove” descends on him. Luke repeats essentially the same details, while Matthew adds later that John tries to stop him from getting baptised, telling the crowd “I have need to be baptized of thee!” Yea, sure Matt.

Robertson doesn’t even include John’s account in the tables, being so different from the Synoptics. But in his version, John sees Jesus and begins proclaiming that Jesus is the “Lamb of God” who will “take away the sin of the world”–referencing Isaiah 53. Wow John, that sure was convinient!

This pattern occurs over and over in the gospels, and Robertson does a good job (not that I guess he intended to do so) of showing visually how this happens. Often, the text in Mark tells the story in such a mimimal way that we get to see a huge wall of text in the Matthew and Luke columns surrounding Mark’s explanation, an obvious sign they have taken some liberties with interpreting the text for their intended audience.

The Harmony doesn’t do any of this intepretation for us though, and I can’t blame him for not doing so. Any explanation of the text would have been outdated in the matter of a few decades, and would no doubt start a religious flame war on Goodreads. </span>

The Illustrated Man

Ray Bradbury

★★★★

The Martian Chronicles were good enough to convince me to read these less famous but just as entertaining short stories. Unlike the Chronicles, this set of stories don’t have a common plot. Years later, I do not remember the stories, but I do remember it being a page-turner. </span>

Broca’s Brain: Reflections on the Romance of Science

Carl Sagan

★★★

This was the first of Sagan’s books that I read, and though it doesn’t manage to reach the quality of his vocal chords, it was what I needed at the time. I was still studying theology, mired in a conspiratorial mindset, checking behind every door for a hidden for clues God left of his existence, mining every news story for signs of the end times. Sagan was the Anti-Conspiracy, the Skeptic before the community had a name, and the chronicler of highly intelligent but slightly insane.

Only a few chapters have stuck with me over the years. In one Sagan spent his time debunking (a topic he probably overdid) a mathematician who spent his time finding evidence of the divine in every biblical number he could get his hands on. In another he discusses Velikovsky’s Worlds In Collison, a fringe theory of a near encounter with the planet Venus which supposedly was the cause of “innumerable catastrophes”–ones that Velikovsky predictably connects to ancient mythological disaster stories.

While Sagan’s analysis of the topics Broca’s Brain deals with might contain an element of timelessness, the topics themselves certainly don’t. His mathematician is only one in a line of thousands of Jewish and Christian crackpots who convince themselves that God directs the integers, rather than a household name, and I wouldn’t trust myself to find a person (who hasn’t read Sagan) that would recognise Velikovsky or his theory. To a reader post-2000s, reading Sagan’s 1979 book simply means explaining unrecognizable, irrelevant topics only to have them dunked on. Sagan is no doubt right about much of what he writes in this book, but if I spent my time writing books combatting fringe lunatics, I’m pretty sure I’d be right too. </span>

Generation Me: Why Today’s Young Americans Are More Confident, Assertive, Entitled—and More Miserable Than Ever Before

Jean Twenge

★★

Another forced book club read, and certainly a book I would have avoided if I had the chance. Twenge deals with statistics throughout the whole book, and yet I am convinced she has no idea just how little she does (to anyone but the most gullible reader) to convince us that her correlations equal causations. This opposite phrase is no doubt uttered somewhere it in the book, a throwaway line to get us to believe that she has considered that possibility, but that in this case, it really is true.

Twenge hardly gets past the most banal accusations that Millenials are entitled and want special treatment, and blames smartphones for a large part of their supposed ills. It reads like your boomer uncle at a family gathering, but the boring conservative one, not the crackpot conspiracy theory one. If someone likes this book, I don’t trust them. </span>

The Old Man and the Sea

Ernest Hemingway

★★★★

One of the great novellas. Not one to be stuck with in an English class though, as one may get discouraged writing about the symbolism of the fish and the boat after you discover Hemingway said there was no hidden meaning after all–the boat and fish was just a fish and a boat.

Hemingway employs the “no chapters” strategy, one Terry Pratchett also loved, but one I am unfortunately no fan of. </span>

## ### </span>